22 Aug TG 2019 Conclusion – The Tortoise and the Hares

(Caveat: if you’re coming to this blog for the first time it won’t make much sense unless you read the two previous blogs.)

A plan never survives contact with the enemy. This is a military truism that is drummed into all soldiers. But, you have to have a plan in the first place to flex around when the enemy does its own thing. In other words, it’s vital you have a plan but don’t ever expect it to work out.

Humans get upset for only three reasons: unfulfilled expectations (things don’t go the way you want them to); thwarted intention (you get stopped from doing what you want); undelivered communication (you want to get something off your chest but can’t). Check it out – the next time you’re upset it’ll be one of these three.

So, I wasn’t particularly surprised or upset when the plan to cooperate with the Ninjas fell apart the very day after we left Briançon. This was a crucial day in getting the Ninjas back on a 19 day track. After the death march to Samoëns on Day 2, Niko had indicated that he intended split the Briançon to Ceillac day into two making it a 20-day gig. But, after the epic 50kms day from Pralongan to Mt. Thabor I was now convinced that we could get to Ceillac in one day – we were fitter and more acclimatised.

So what wen’t wrong? Actually, nothing went wrong from a human relationship point of view. They were simply much faster uphill than me and I couldn’t keep up on a moment by moment basis. The long and very boringly arduous afternoon climb to the Col de Fromage (yes, really!) when they streaked past me and left me plodding on on my own was the moment I knew that if it continued like this for the next seven day’s life wouldn’t be much fun. I had this crazy thought, ‘Okay then, if that’s the way it is, then Alpine Ninja Training School is over. It’s time for the final test exercise. You’ll have to chase the old man down to the Med.’ I was going to break out and make a solo dash for the coast and beat them to it.

I had other reasons for wanting to do this: a) I’d initially set out to do this on my own before being drawn into the Ninja’s plan; b) I’d also quite specifically stated on the TG website ‘as fast as possible’ (although the Ninjas were fast moment by moment they weren’t maximising the potential for each moment of daylight); c) I’m better as a solo operator; d) I wasn’t fully out of my comfort zone.

On that last point, I was specifically interested in how hard and far one can push a 56-year-old body. I was very inspired the previous year when two former Parachute Regiment officers, Neil Young and Peter Ketley rowed the Atlantic. So what? Well, they were grandads, in their 60s and they smashed the record! (BTW – this was first done by two other Paras in 92 days in 1966 in a 20-foot open dory called English Rose III – John Ridgeway and Chay Blythe). So, I was keen to put myself well outside the comfort zone and stay there. I wanted to see what my limits were.

What was now unfolding should not be in any way seen as a criticism of how last year’s GTA had been organised by Richard Villar and Godfrey McFall. Each day’s hiking was challenging in its own right – Richard was writing a book, I was writing a blog most evenings and the Fools like a good hike with a decent meal, drinks and socialising. All normal, balanced and sane. My aims in deliberately pushing myself outside the comfort zone were to convince donors to contribute to Children With Cancer UK and to see what I was still capable of – is 60 the new 40 as Neil Young and Peter Ketley demonstrated? What are the limits of human endurance? Which dominates – mind or body?

So, when I finally staggered to the top of the Col de Fromage my plan was set. The Ninjas were resting there, which made me all the more determined not to have a repeat performance of a day in which we’d started together and I’d got left behind. So, I pushed on and we agreed to meet in Ceillac in the valley below.

The big advantage I had was I knew their 19-day plan and their MO. Their days ended at places low down. They liked to have beers in the evenings. Their stop points were to be: Larch; St. Etienne de Tinée; Refuge de Longon; St. Dalmas du Plan, and from there on the GR52 – Le Boreon; Refuge de Merveilles; Menton = seven days. I also knew that they got up at 5am and started walking at 6am.

The other limitation was their kit. The upside of being minimalists and carrying very light packs is speed and less energy expended. The downside is they had no spare capacity, limited ability to really survive high up. The less gear you have the less flexibility and the higher the risks. Their hiking poles, for example, became the structure for their flysheet tents. It’s clever dual use of gear, except if you lose/break a pole you also lose your shelter. By contrast, I had a small standalone tent, a bivvi bag, and a survival bag. I also had gloves, spare clothes (which were to become vital when things turned messy later on – more of that later) and other bits and pieces that would enable me to stop anywhere.

Of course, the other massive advantage I had was I knew exactly what lay ahead and roughly how to pace it. A crazy idea took hold in my head – I’d beat them to the Med by a day. 18 days. So, I had to do their next seven days in six. Or, to put it another way, I had to do what had taken us 13 days the previous year in six. A very very tall order.

The plan was very simple: get ahead initially; get up an hour earlier than the Ninjas do and start walking an hour earlier at 5am; have no specific end of day destination. My daily destination would be last light. I’d therefore tab (see previous blog for definition of tabbing) for 15-18hrs per day and sleep the rest. And repeat.

As the Ninjas had their beer and I had a Coke in Ceillac they said they’d camp somewhere along the river. ‘Ah, well, I think I’ll push on a little higher. I know somewhere up there on the way to the next col that is a lovely spot.’ I knew they wouldn’t follow me up as beers were quite important to them if I could get up to Lac Miroir, a stunningly gorgeous spot to camp I’d spotted the previous year, by last light I’d already be two hours ahead. But, they’re faster uphill so make that 90mins.

‘Okay. Well, we will see you in Larch tomorrow?’ Another of their valley beer stops.

‘Possibly. But I may move on a bit depending on how I feel. Let’s keep in touch by text.’ I had every intention of getting as far beyond Larch as I could and slowly and incrementally increase the gap. But, I wasn’t going to tell them that.

Sevrine was a little surprised when I said that. And I said something about our pace being so different that it makes more sense to split up loosely.

Was this the treachery part of ‘old age and treachery will always beat youth and exuberance’? No! Treachery is throwing their boots away or breaking their hiking poles. This was just levelling the playing field somewhat.

Also, the Ninjas are bloody competitive. I got a hint of this much earlier when one morning at the Refuge de la Croix du Bonhomme we’d agreed to leave at 6am for Landry. At six they were still filling water bottles so I just took off saying, ‘You’ll catch me up.’ They left twenty minutes later but failed to catch me up a particularly savage ascent. When we finally stopped at a refuge for lunch Niko admitted he’d spotted me and timed the interval and at one stage they were five minutes behind. Anyone who does that can only intend to close the gap. So, there was little doubt in my mind that once they twigged to what was going on they wouldn’t be slow in closing that gap.

But, in fairness to the Ninjas they had no idea at all they were in a race. Nor did I tell them. The race for all of us was really against the clock – 19 days for them and 18 days for me. The idea that I’d be chased and hunted down by them was purely a fiction created by me to act as a motivator. Nothing focusses the mind more than being hunted down. They were more than capable of running their own gig and I needed to run mine.

That night I slept in a bivvi bag under the stars up at Lac Miroir waking early and moving on to get over the next col by 7am followed by a long downhill. As the day progressed I began to imagine the more nimble Ninjas closing the gap. Their ability to move fast uphill could easily undo any slim advantage. Ask anyone who had been hunted by a Hunter Force and they’ll all tell you that the reality takes hold very quickly. It’s called paranoia. I spent most of the day looking over my shoulder, half expecting to see two tiny white back packs drawing ever closer. The thought alone kept me moving as quickly as I could.

By 5pm I’d got to Larch, refuelled on Coke and ice cream and moved on into a cooler and faster evening tab, initially up a road, and then further and further up a valley as far up against the next col as I could get – 13kms from Larch, a significant time and distance edge on the Ninjas, whom I knew would stop in Larch itself.

The following morning I was up and over the col by 6am. As I crossed it I got a mobile signal and with it a message from Sevrine from the previous night, ‘Hey, we’re in Larch having beers. Everything alright?’ I replied that I was close to Bousieyas but the message failed to send. And so, I just kept going and going and going, stopping only for half an hour to dry out gear.

Disaster struck at approximately 2pm that afternoon. I stopped in St Etienne de Tinée and had a pizza and several Cokes thinking I needed the fuel. In fact, I poisoned myself and within an hour had the most shocking case of diarrhoea. In fact, I’d never experienced anything like it. I thought a couple of Imodium Melts would sort it. Not a bit of it. I took four. Snake oil!

I’ve thought quite a bit about including this detail in all it’s awfulness and elected to share it because if there was ever a showstopper this was it. I couldn’t keep anything in without spraying it all out like a farmer’s muck-spreader. The heat also was intense which didn’t help. Slowly and very uncomfortably I made it to Roya. Without getting that far I wouldn’t have a chance of hitting St Dalmas du Plan the following evening – a massive leap forward and the critical junction where the GR5 turns south to Nice and their GR52 hooks north back into the Mercantour National Park and, through a massive right-handed arc, curves south through some of the toughest terrain on the GTA, incomparable to the GR5. I needed to get to St Dalmas du Plan the following evening to give myself the bare minimum to get to Menton from there – three days. Also, I knew that if I got there the Ninjas would be at Longon a full but short day behind me. Game over, you might say. Not with the Ninjas.

But, the schlep from Roya was long and very hot, interrupted by the need to stop and wash soiled clothing and gear. Everything smelled of shit. I was followed by flies. Furthermore, the descent from Refuge de Longon to St Saveur sur Tinée in that afternoon’s blistering heat with a leaking arse was intensely emotional.

Most people think going up mountains is hard and coming down them is easy. It’s the other way round. Going up is easy and controlled. Going down is like trying to avoid an uncontrolled descent – constantly on edge and in a state of pain and tension. Vets of the GTA can reel off the horrendous descents: Col de Golaise; Les Houches; Landry; Modane, St Saveur sur Tinée etc. The latter is uniquely steep, long and uneven. I have a picture from last year of Godfrey McFall sitting on an iron bench outside the cemetery in St Saveur just where the descent ends. He’s gripping his poles and looking intense. I must have had an easier descent last year but this year in the heat with swollen feet I found myself shouting aloud, ‘Not more fucking cobble stones!’ just as I turned the corner to reveal the bench. I collapsed onto it and tore off my boots and socks. I completely get it, Godfrey!

Looking after your feet on something like this is more important than your arse. Feet are everything. They boil over in hiking boots really quickly. It’s vital to stop and cool everything down – dry out sweaty socks, take out insoles, air boots, cool and dry feet. My boots got so hot, I’d half submerge them in rivers to accelerate their cooling. I’d always plunge my damaged and inflamed Achilles in an icy river to cool it down. And the start all over again.

On one blissful occasion, completely alone I found a deep pool in a fast flowing river and stripped everything off, rinsed and washed all my gear and cooled down in the icy water. Within an hour everything was wringing wet with sweat and ponging of shit. Deep joy.

That day’s push to St Dalmas du Plan took 18 hours. I finished the last few hours with a head torch. I’d set that as my destination to jump off onto the GR52, for the last three days. Failure to reach St Dalmas would have meant the difference between 18 and 19 days.

And yet, all this was self-imposed. If you look back at the last blog I pose the question whether we’d complete this in 20 days. No mention of 18. I could have taken my foot off the gas, throttled back, had an easier time and no one would have been the wiser. Except me. For me, the biggest aspect of this was setting myself tough daily goals, often measured in 40 or 50+ kms, and holding myself to them. This was a much bigger deal than racing the Ninjas. It was 18 days shit or bust. I wanted to do it in half the time Richard and I had done it the previous year, rest days included.

Unfortunately, the shit thing became a massive cause for concern. A potential show-stopper. Eventually, I decided to stop eating altogether and did the last four-and-a-half day’s without food. Water, sugary tea and boiled sweets became my only energy intake, and of course my own body fat and muscle. Oddly, when I stopped eating I experienced no decrease in performance or additional fatigue. The mind controls the body not the other way round.

Two things dominated my waking moments – the constant hunt for water – I had a small silicon cup for drinking from safer sources on the hoof and a Sawer filter through which I could suck up filtered water from less certain more stagnant sources. Water was my fuel. As soon as I stopped eating things got better. I got control over my body again.

The second constant preoccupation was a constant cyclical pattern of time-distance-capacity calculations: if I could make it to X then Y would be within reach – do I have the legs, light, energy etc. etc. etc. Ceaseless calculations.

A good proportion of the additional weight I was carrying had to do with keeping devices powered up – phone (for navigation using the Gaia GPS app) and the Garmin GPS MAP 66i InReach device which squawked to the Iridium satellite system every 30 mins allowing followers and donors to monitor progress. My solar panel went tits up in Tignes and I literally put it in a trash can. No point carrying extra weight for no purpose. So, I was reliant on a couple of hefty battery packs to keep things going.

I am amazed by the InReach technology in the Garmin. For a modest monthly fee it’ll track and plot me for the world to see and allow me to send and receive messages via Iridium. I saw its potential for engagement in fundraising immediately.

In fact, I tried something similar 14 years ago during the Greystoke Mountain Marathon in 2005 when I raised money to build a school in Sri Lanka after the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami devastated the village of Seenegama in Sri Lanka. Originally devised by Lt Col Peter Jones OBE as the 202 Tops Challenge in 2002 it essentially involves going over all 202 mountain tops in the Lake District National Park in under 240 hours. Total distance is about 300 miles and 100,000′ of ascent and descent. I couldn’t do it with Peter in 2002. So he and his adjutant did it together. At the time the fell running community and Cumbria Mountain Rescue deemed it impossible. They were wrong. In 2005 I did it solo. At the time I thought it would be great if donors could track me online. This involved merging donated digital mapping from UK’s Ordnance Survey, a massive white brick that some ex-UK Special Forces guys from SRS International gave me to carry, and a very clever guy in Florence called Ben Hammersley who wrote the code. It almost worked but I carried a 5lb brick around the Fells to no real benefit. Fourteen years on and you can buy this capability straight off the shelf and anyone in the world can follow your trail of 30 min breadcrumbs.

So, I’ve been pretty fastidious in keeping the Garmin gear charged up and functioning, always posting an end of day message. The great plus about this system is the risk management side of things that it offers. It has an SOS button (otherwise known as the Babes ‘n Beer button). Depress it for three seconds and the device flags up in New York triggering an international rescue. You’d better have a damn good reason for using it, i.e. a real emergency and not just to get out of some shithole back to the babes and beer. But, what a great aid to mountain safety and risk management.

So, I got to St Dalmas du Plan with an empty belly and my arse on fire, stinking of shit. My last proper shower and shave had been eons ago in Plampinet, before Briançon. I was gungy, 3 PARA gungy. And I had three days to get through the GR52 to Menton – something that had taken us seven days last year. It is bloody tough terrain. It is quite unlike the GR5. It’s simply not a regular hiking trail. The peaks are jagged, close together and trail-less. Often you are bolder-hopping hour after hour either uphill or steeply downhill. It slows everyone down. It’s brutal. I knew that the only way to slice it up into three days was to push as far forward each day. On day one well beyond Le Boreon and on day two to get to Camp d’Argent, from which it’s ‘only’ about 43km to Menton.

On the first day out I got beyond Le Boreon high up to a lovely lake. I’d aimed to get over the col, leaving me one less to do the following day. But time and low clouds thwarted me. Nevertheless, I slept up against the col and was over it by six the following morning. That second day dissolved into a nightmare of five cols in total ending in another head-torch arrival at Camp d’Argent at 11pm. I’d passed through Refuge de Merveilles for only as long as it takes to buy three Cokes and decant them into a litre container. The refuge is as rank as as it was last year – a biohazard. I was glad to get over Devil’s Col and down to Camp d’Argent. From there I knew I’d make it to Menton the following day, rolling into one what had taken us two days the previous year.

Throughout this the heat had been intense during the day. My fastest times had been in the cool of the early morning and in the evenings and nights. Between 11am and 5pm the intense heat was battering. My only real protection was a regular intake of water – up to 8 litres per day and my trusty camo bush hat which I’d soak as often as I could. The evaporation effect acts in the same way as a fridge to keep your head and brain cool. In days of yore the British Army used to issue 38 pattern webbing. The water bottle had a felt cover. This was designed to be soaked and the evaporation effect kept the water bottle’s contents cool. Clever.

The heat on the last day was blistering. It simply was not a case of cruising to the end downhill. A long bash from Camp d’Argent leads to yet another agonising descent into Sospel. En route I was ‘attacked’ by three fearsome French sheep dogs – the kind that are bread to kill wolves. They are truly scary. Signs all over the national parks warn people to stand stock still, not to yell at the dogs and not to throw stones at them. Easier said than done when they’re snarling and barking. So, my route to Sospel was blocked by hundreds of sheep and three hell dogs who rushed at me as soon as they saw me. Surrounded and trapped. As luck would have it the former manager of Battersea Dog’s Home had taught me doggy calming signals. These involve looking away from the dog’s eyes, lowering your head in submission and blinking your eyes very rapidly to say ‘I’m not a threat’. It had worked on my two previous encounters with these creatures on this trip. But, on this occasion they paid not the slightest attention to my doggy language. One shoved its nose so far up my arse it was almost rape and the other found my crotch just as interesting. Clearly they were more interested in these awful smells than than tearing my arse and balls off. ‘Oi! Fuck off! That’s rude. Get your snout out of there!’ I was slapping them away. Before I knew it I had three interested friends trotting after me like lap dogs. The shepherds looked on slightly bewildered and scratched their heads. I shrugged and said, ‘They like my arse.’ Chronic diarrhoea can have its upside in a weird way.

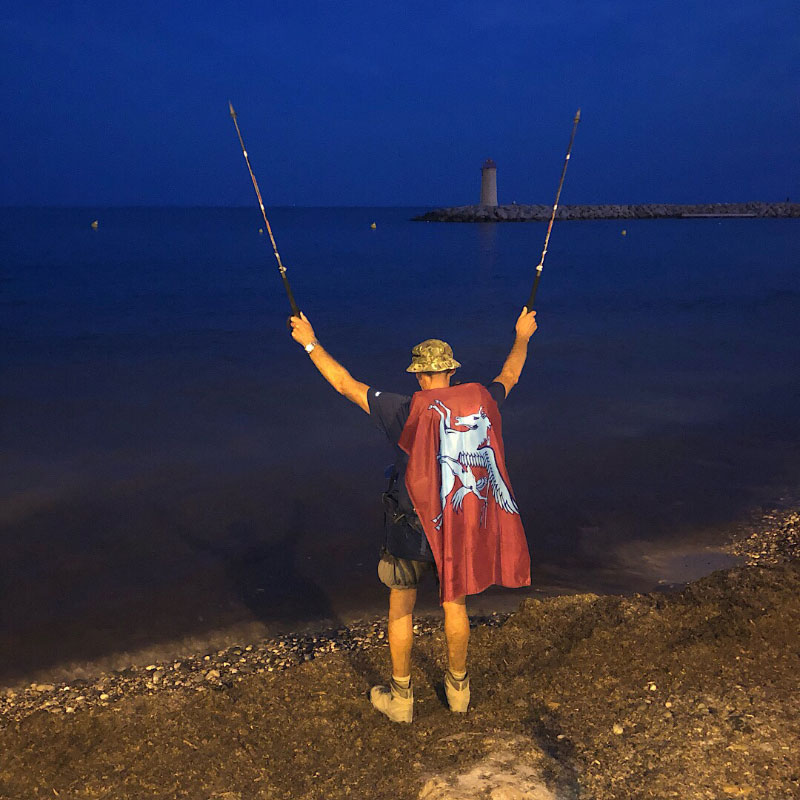

Having avoided doggy rape I made haste to Sospel – be-caped I might add. This is the 75th anniversary of both the Normandy landings and the Battle of Arnhem during which British Airborne divisions jumped into Europe to liberate her from Nazism. On that basis I’ve been carrying the flag throughout this trip. As this was the last day I draped it over my pack – a kind of morale-boosting go-faster Airborne Caped-Crusader thing. And thus swooped down into Sospel during another heat-crazed foot-swelling descent. 20kms to go.

In Sospel I took an hour to cool the feet and boots down and stock up on proper doses of Imodium. Real capsules and not those snake oil so-called ‘melts’.

The last 20kms to Menton are far from easy. The heat and humidity were oppressive as I set off at 3pm. I was anxious to get to the end before dark so hoped to cover the distance in five hours. But the heat and an unavoidable pit stop delayed that. Two-thirds of the way along the route there’s a permaculture garden which invites hikers to help themselves to free soft drinks – locally made concentrates and lemonade. We had stopped there the previous year and helped ourselves but had not left a voluntary contribution. On that occasion the lady running it had waved from an upper terrace. This time she was right there with her Collie dog. Her name is Christine. She is German but has lived in France for 45 years working as an actress and singer before turning to permaculture and tending to this exquisite oasis. We chatted. I drank ‘kir’, a local lemonade. I could have stayed longer. When she went off I put €20 in her tin to make up for the last year.

I had more more climbing to do. You work your arse off to get to Menton. Up and up you go as the clock ticks on. It was 7.45pm as I began the final notoriously steep and lethal descent with Menton visible below. In my haste to get off that mountain before dark I fell three times – badly. Once, so badly I ‘woke up’ wondering what had happened, with a left jaw that felt like it had been punched by Mike Tyson. Needless to say my bowels didn’t take kindly to this rushed, slithering ankle-snapping descent. I was a filthy mess as twilight closed in and the lights of Menton still seemed far off. 9pm was now the target. Eventually I was off that monster and running down Menton’s steep steps and streets, past the marina and on towards the small postage stamp-sized beach where we’d ended last year. At 20.55 my boots touched the Med. 17 days, 20 hours, 55 minutes. 650kms and 40,000m of ascent. But, subsequent analysis of the Garmin and daily Strava readings showed the true distance covered to be 742.44km (464.03 miles) – an average of 41 kms or 26 miles a day.

I asked a couple near the beach to snap a photo and then I was completely on my own with nothing to do. I sat there for an hour before moving.

No hotel would have me. I can’t blame them. I looked and smelled dreadful. As it happens, a campsite is only a ‘short’ climb up a massive hill – 300 steps! I staggered up them to find the blockhouse open. I had a shave, a warm shower, and I washed all my honking stinking clothes, then blew up my ThermRest and fell fast asleep under an apple tree on a warm night with a gentle moon.

But, what of the Ninjas? The next day was Day 19. The plan that they’d been following had them hold at Le Boreon. If they’d done that they could not have got along the rest of that hellish rollercoaster in two days. I fretted that they’d miscalculated how hard the GR52 would be and how unlike the GR5 it was. Perhaps I should have stuck with them? I dropped Sevrine several texts that day to warn about the descent to Menton and lack of hotel rooms. No answer. I feared that after all that effort they might have slipped to arriving on Day 20.

It was never really a race between us. I’d concocted that to spur me on to achieving 18 days. But, we were all up against the clock. What really appeals to me about these youngsters is that they set out on their first grand adventure with their own ideas about how to do it, what to carry, often making their own gear, including the tents. They don’t just talk the minimalist talk but they actually walk it and and are prepared to experiment with it on a massive learning curve. I wasn’t the only one prepared to step beyond the comfort zone. They are bold and courageous. They deserved their 19 days. As the day wore on into the night I feared they’d lost their race.

I awoke this morning to a text from Sevrine: ‘Arrived yesterday at 6pm in Menton from Camp d’Argent’. They’d done it in 19 days and only 21 hours behind me. More importantly they’d clearly worked out how to cover the GR52 in three days. They didn’t need me to help them figure it out. Fully-fledged Alpine Ninjas.

We met for lunch today. As they arrived at Bar Inky I said, ‘What kept you?’ And then hugged them both. We discussed kit, tactics, what worked, what didn’t. They’d ticked along magnificently and enjoyed their beers along the way. Niko had properly assessed the need to push along the GR52 as far forward each day. Their original plan had been to strike to Menton from Refuge de Merveilles – an extra 13.5kms. On top of 43kms from Camp d’Argent that would not really have been possible in a day with kit. I am thrilled that they they revised that, succeeded and did it themselves on their own terms.

And that is how we did that! No one beat anyone. We were all winners in our own plans.

I’d like to thank everyone who has followed this saga and in particular to those who donated to Children With Cancer UK. To those who haven’t donated and are thinking of doing so, please do – go for it. Kids die of cancer every day.

Also a big thanks to Ben Clayton-Jolly and his partner Sigrid Ragossnig who fed me in Les Houches and provided much needed encouragement along the way. And also to Rupert Hanson in Canada for his continued technical support.

But, my biggest thanks are reserved for Sevrine Fontaine and Nikolai Kondryataev, without whom this story would have been so much blander. Thank you both for being a vital if unwitting part of it and in helping to raise money for children’s cancer. Your contribution has been bigger than you know. So, thank you! I wish you all the very best in your future Grande Randonnes and you’re always welcome in UK – mi case e su casa. Oh, I failed to mention today, as Chief Instructor of the Alpine Ninja Training School I am pleased to to tell you that you both passed, cum laude.

It’s odd how things work out. Today is the 22nd of August. It’s nearly over. My niece, Tatiana, died in the very early hours of 23rd August 2017. I’m glad we were able to honour her by completing Tatiana’s Gambol 2019 in these past few days in the way that we did.

God bless you all!